Coyote~Wolf~Bear

The Coyote~Wolf~Bear Education Initiative is a partnership with a shared vision of bringing wildlife coexistence strategies to communities across Ontario.

To foster coexistence, we are committed to providing the public, elected municipal leaders and other community stakeholders with effective tools to navigate the science behind wildlife biology in real-world scenarios. We can provide accurate information about behaviour, risk management and non-lethal conflict solutions that support people, coyotes, wolves and bears inhabiting a shared landscape.

Budget cuts continue to limit the provincial government’s capacity to engage directly with concerned citizens to solve and mitigate wildlife conflicts with programs such as Bear Wise. Urban and rural entities are now forced to assume responsibility for managing wildlife interactions without preparatory training or a solid background of science-based mitigation methods. This highlights the need for more innovative and progressive educational outreach such as the Coyote~Wolf~Bear Education Initiative.

As paradigm shifts in conservation science bring ethics to the forefront of wildlife management, we underscore the importance of minimizing wildlife encounters. Facilitating non-lethal, sustainable strategies for communities through education promotes awareness and appreciation for wildlife. Removing the 'mis' from misinformation. Learn more at Coyote Wolf Bear Education Initiative.

Learn About Bears

North America’s Song Dog: A Champion Ambassador for Co-flourishing

Coyotes are the epitome of a reliable “eco-thermometer” for any community in which they inhabit. Coyotes put us all on notice when they get too comfortable around people because of human indifference and misunderstanding about this family oriented, social and highly adaptable canine. In other words, when communities experience conflict, much can be learned from the presence of coyotes on how to become better stewards and citizens. Coyotes, a keystone species, are one of the most persecuted animals in North America. With little protection through lethal management policies, coyotes are destroyed without any policy accountability. Known as North America’s song dog, their brilliant vocalizations have graced ancient lands since the Pleistocene era. Coyotes are a respected part of Native American storytelling and hold a sacred place in many cultural traditions today.

One of the most misunderstood and maligned native carnivores, the coyote has been persecuted throughout history in North America and yet has aptly adapted to living in diverse ecosystems including populated metropolitan centers such as Toronto, Canada and Chicago in the United States.

Meet the Eastern Coyote

The scientific name for the coyote is Canis latrans (western coyote).

They are part of the Family Canidae which includes dogs, wolves, foxes, jackals. The Family Canidae is referred to in general as the canids.

Genetics from the Algonquin wolf (Eastern Wolf) and Western Coyote hybridization has evolved into what is commonly referred to as the Eastern Coyote. A rich genetic blending which has led to the Eastern Coyote (e. coyote) often being referenced by scientists as Canis latrans x lycaon and/or Canis latrans var.. This unique and historically significant species began its evolution over a century ago filling an ecological niche. Weight ranges for the slightly larger cousin to the western coyote, are on average between 22- 41 pounds. The coyote is significantly less in body mass to the Algonquin wolf.

Coyotes form highly social and structured families also called packs. Family members share in the hunting, pup rearing and territorial protection duties. Intact, established packs are capable of hunting larger ungulate prey targeting weakened, unhealthy herd members. Pack size varies depending on habitat, available food sources, and human impact (urban/rural). Our past research concludes 2-3 adults, and pups, however, variations in family size fluctuates due to habitat, forced migration, available food sources, and mortality rates.

When the breeding or alpha pair is left to thrive, they mate for life. Younger more inexperienced pack members have the potential to start breeding within the first year of life if the alpha pair dies. Coyotes demonstrate a diligent and committed co-parenting style. The alpha male provides the necessary nourishment for the female during denning including regurgitating food for (pups) to consume. Coyotes demonstrate excellent skills as solitary/pair hunters and when rearing pups the alpha male will provide much of the food. Parents are key facilitators in teaching appropriate hunting skills to the pups. Juveniles may disperse in the fall or later during the following spring to establish their own territory. A yearling or beta, may also remain with the pack to help rear next year’s pups. The Creekpark Pack demonstrated this behaviour over a two year period.

Alpha males have been observed leading solitary lives after the death of the alpha female mate. ‘Lone’ or transient individuals may utilize buffer areas around an established territory; however survival is more difficult for these loner animals. Vocalizations such as howls, barks, throat growls, yips and whines are used to communicate between pack and non-pack members; defending territory, distress, warnings, celebration, to locate pack members, mating and mourning. Brief periods of interaction include mating and pup rearing events between former members of the dispersed Creekpark Pack. During field research our observations demonstrated that vocalizations and proximity tolerance to one another increased during these times.

Although coyotes are classified as carnivores, their foraging and hunting behaviour is described more accurately as opportunistic omnivores. They readily utilize carrion (already dead animals) wherever possible; however, their diet consists of mainly rodents, rabbits, fruit, berries, insects, and geese (eggs). Coyotes can become accustomed to livestock when proper farming methods are ignored. The lack of dead stock removal is a reliable attractant for all carrion feeders, especially coyotes. This can set the stage for future depredation of living stock when good husbandry is ignored.

Community Coexistence

Coyote sightings are not uncommon in Southern Ontario. Coyotes have been a vital part of our ecosystem for many years. By applying common sense, preventative techniques and by being aware of the diversity of wildlife that we share our community with, we can minimize human and wildlife encounters and conflict. When coyote sightings increase many times these sightings are due to humans intentionally or unintentionally providing a food source and also multiple sightings of the same coyote. Over flowing bird feeders, mishandling of compost, and fallen fruit attract a diverse range of prey species such as rodents, squirrels, chipmunks, insects which coyotes will utilize as food. Consider that the birds and small mammals that frequent bird feeder stations are potential prey food for other predator species such as owls, hawks, fox and domestic pets. New infrastructure such as roads, fences and urbanization impacts how wildlife moves throughout our communities. Urban boundary expansion creates a loss of habitat and green spaces for wildlife.

Common precursors to an increase in encounters and conflict between people and/or dogs are often evident when anthropogenic food sources are present in the landscape. Allowing pets to roam unattended and dogs off leash in green spaces can elevate the risk of encounters and conflict between a domestic dog and wild canine. Intentional or otherwise, feeding coyotes and other wildlife species puts wildlife and pets at-risk. There is a direct impact on canid behaviour including coyote’s returning to a site to access food sources. One step to discourage citizens from acclimatizing canids to a human food source is to implement a Feeding Wildlife By-Law. Communities across Ontario recognize this by-law as an effective, sustainable approach that fosters awareness and responsible stewardship. The ultimate outcome is coexistence.

As an enforceable tool for prevention, implementing a Feeding Wildlife by-law is an accessible option for communities and is another educational strategy that supports front line response personnel such as Law Enforcement, Animal Control and Humane Societies. This type of by-law promotes community engagement and awareness about how to maintain attractant-free businesses, backyards, parks and trail systems.

Coyotes are an integral part of our diversified ecosystem and provide a necessary and healthy prey/predator balance.

Benefits to a farmer—Coyotes keep meso-predators such as fox and raccoons in check and can potentially minimize crop damage by hunting abundant rodent populations. Predator friendly ranching/farming techniques such as incorporating Livestock Guard Dogs (LGD), range riders, night shelters and deploying non-lethal strategies that maintain pack stability prove successful in creating practical and peaceful coexistence between people, livestock and predators.

Mortality rates are very high for Eastern coyote families with humans having the highest impact, vehicles second. Education initiatives, wildlife proofing property and safety tips that include a factual overview about coyote ecology is beneficial for communities in which they live.

How You Can Help Foster Compassionate Coexistence

* Educate yourself and your community about coyotes.

* Please share our print resources with family, a neighbour, naturalist groups, city officials, educational institutions, law enforcement and animal response personnel. Our coyote information is available to help create compassionate coexistence in your community: Educate. Engage. Empower.

* Be inspired to organize a Co-flourishing with Coyotes and/or Coyote Wolf Bear Education Initiative event in your community. Contact us to request one of our Coyote Watch Canada (CWC) Outreach Representatives or let us know how we can help to support your local event. Our resources are free to share at the venue.

* Champion nature literacy by spearheading an arts and literature compassionate wildlife event featuring local artisans and musicians to promote appreciation and community resiliency.

* Become a strong informed voice for coyotes and other urban and rural wildlife by writing to the media, promoting non-lethal conflict resolution policies to address people and wildlife encounters.

* Encourage city and park officials to endorse and post our beautiful and informative Coyote Awareness Sign or Poster (pictured above).

* Consider joining our CWC Team by inquiring about volunteer opportunities or citizen science efforts.

* Community support through volunteerism is the heartbeat of our organization and the successes we achieve together.

To learn more about this resilient and ecologically significant wild canid please visit coyotewatchcanada.com.

Pertaining to the content and photos on this page about coyotes – © Coyote Watch Canada

Coyote~Wolf~Bear Initiative logo by Tabitha Buschkiel

Eastern and grey wolves have similar life cycles

Wolves are social animals

Two of the most iconic characteristics of wolves are related to their social nature: cooperative breeding and cooperative hunting. Both species of wolves typically live in packs – groups of related individuals. There is usually only one breeding pair within the pack, often termed the alpha pair. The rest of the wolf pack is made up of related family members – offspring and sometimes siblings of the breeding pair. The breeding pair is usually unrelated – wolves regulate their own diversity if they are able to find unrelated animals to breed with on the landscape. The pack is a dynamic group, and takes part in both the yearly raising of pups and hunting activities. Pack members spend a great deal of time socializing with other family members, and display great variation in temperament, or personality.

Cooperative Breeding

The breeding pair, usually monogamous, asserts its dominance over other members in the pack in an effort to prevent other wolves in the pack from mating. Without enough prey, multiple pup litters would not survive. Where prey is very abundant, it is more common to see 2 litters of pups within a pack.

The breeding pair spends a lot of time in courtship leading up to their mating, which generally occurs in February depending on where the wolves live. Pups are born about 63 days later in a den that may have been used many times by the same pack (perhaps even for hundreds of years). Born deaf and blind, they remain in the den for about 3 weeks before emerging and learning to play, hunt and travel with various members of the pack over the next several months. Females other than the breeder are known to lactate and cooperatively nurse pups within their pack. The whole pack is engaged in raising the pups; to wolves, family is everything.

As the pups age and the pack begins to travel further from the den as a group to hunt, pups are often moved to areas called rendezvous sites where they will be protected while most if not all adult pack members are away hunting. Pups begin travelling with the pack members on hunts in the autumn and winter, learning cooperative hunting techniques needed to become important contributors to the pack health in the future. Over the next year, pups may disperse from their pack, searching for new territory and potential mates in the surrounding landscape. Those individuals who remain with their parental pack often assume den preparation and babysitting duties for the pups born the following spring. In this way, the great family cycle continues.

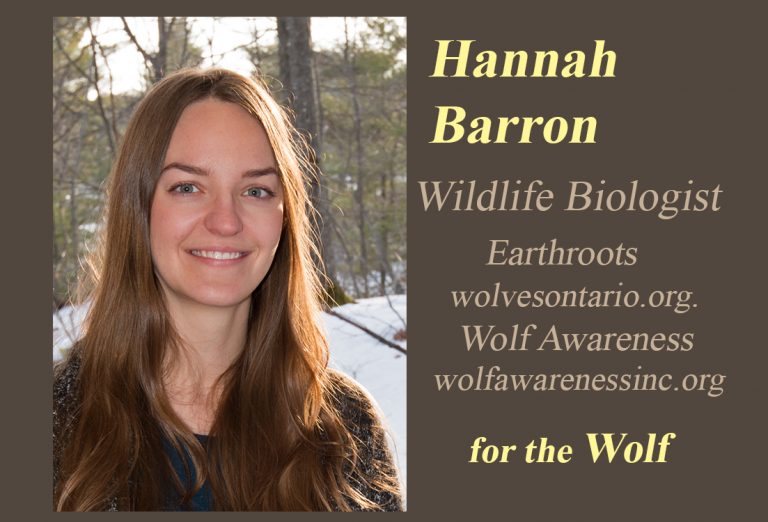

Learn more about the wolf at: http://wolvesontario.org/wolves-ontario/

– A bear is an omnivore, however it is classified as a carnivore, yet the black bear is primarily a vegetarian.

– Very intelligent mammal. Intelligence rivals that of the great apes.

– Extremely acute sense of smell. Scent oriented mammal.

– Good eyesight, similar to humans, bears see colour.

– Cubs stay with mother for minimum 1.5 years.

– Cubs learn by following mother, mimicking her actions and activities.

Bears inhabit a sensory world that is fundamentally different from ours. We are sight oriented animals, depending principally on the extremely fine discriminatory vision. Bears are scent-oriented: they determine their path through the world largely by determining what it smells like. For all mammals, the acuity of the sense of smell depends primarily upon the size of the olfactory mucosa, a specialized area of mucous membrane located in the nose. In humans, the olfactory mucosa normally totals less than a square inch in area. In the average bear, it may be one hundred times that much. If the wind is right, a bear can smell you coming when you are still over a mile away. Despite its strong reliance on its nose, however, a bear’s other senses are as good as or better than our own. Bears can pick up the sounds of normal human conversation over a distance of nearly a quarter of a mile, and will usually come alert at the click of a camera shutter half a football field away from them. Their hearing, like that of a dog or cat, appears to range well up into the ultrasonic frequencies (blowing one of those “silent” dog whistles in bear country is probably not a particularly good idea). Their vision is also acute. This flies in the face of popular wisdom, but it happens to be true. Their shape and color recognition ability is excellent, better than that of chimpanzees and other close human relatives.

Omnivores are opportunists, will happily feed on any trophic level, as readers may discover for themselves if they go feast upon a steak smothered in mushrooms with a glass of wine and a side order of salad. A bear would enjoy that meal every bit as much as you would, and would probably take it from if it had the opportunity. An omnivores niche – to mix sports metaphors a bit- is that of the pinch hitter. Whenever another animal falls down a bit on the job, or leaves its niche temporarily unfilled, the omnivore is there to take up the slack. The key to this niche is flexibility, and the key to flexibility is intelligence. An omnivore must be able to recognize opportunities for food, even when they come in unfamiliar guises. It must be able to adapt its diet to what is available, meaning that it must be able to conceptualize the idea of substitution: if you can’t catch the squirrel, you substitute the nuts in the squirrel’s storehouse. It must be willing to experiment with new foods and be able to carry out those experiments in ways that won’t harm it (discovering that a plant is toxic is of very little value to an animal that dies in the process of making this discovery). The animal must above all be able to learn easily, both from its own experiences and from the experiences of others of its kind. It must be able to build up a specific, individualized body of knowledge that is uniquely tailored to its own peculiar environment, the distinctive combination of biocenters and travel corridors that makes up what it has taken for its home,range. Instinct cannot be tailored this way. Generalized knowledge can be passed on by the genes, but specific knowledge must be taught. This intense need for learning colors everything about an omnivore, right down to the level of biological reproduction.

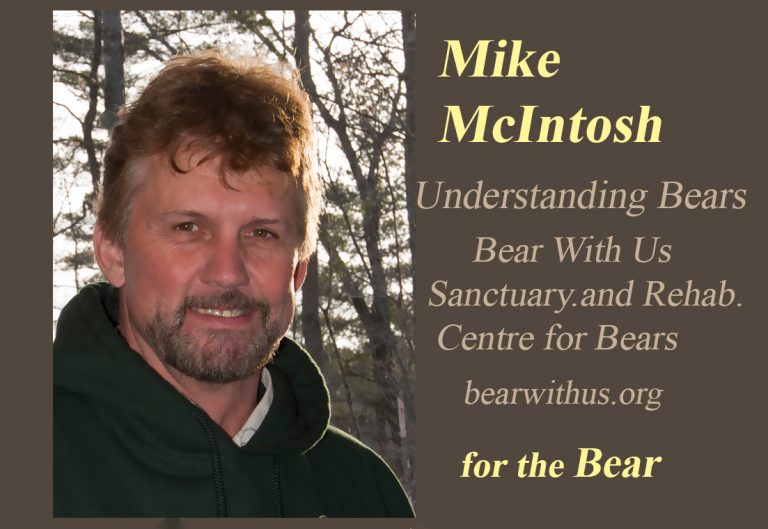

Learn more about the bear at: www.WiseAboutBears.org and throughout this website: www.bearwithus.org

Credits – Referenced from a book entitled: Bears -Their Life and Behavior by William Ashworth Published by Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, Information Tidbits by Mike